Many families face a confusing reality: their child shows signs of ADHD, but anxiety seems to be at play too. Understanding how these conditions overlap can help you find the right support for your child. What we'll cover in this article: Why ADHD and...

How to Talk to Parents When You Suspect Autism

A Teacher's Complete Guide to Sensitive Conversations

Medically reviewed by Nicole Garber, MD, Chief Medical Officer

As an educator, you've developed an intuition about the students in your classroom. When something feels significant, it usually is. But knowing how to talk to parents about autism concerns is a different skillset altogether. You might worry about how they’ll receive your observations, or feel uncertain about your role in this process. This guide will help you prepare to have a productive conversation with parents and support your student’s development and learning.

In this article, you will learn

Understanding the weight of your observations

Research shows that early identification and intervention can significantly improve outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Your observations provide important information that, alongside what parents see at home, creates a more complete picture of a student's developmental needs.

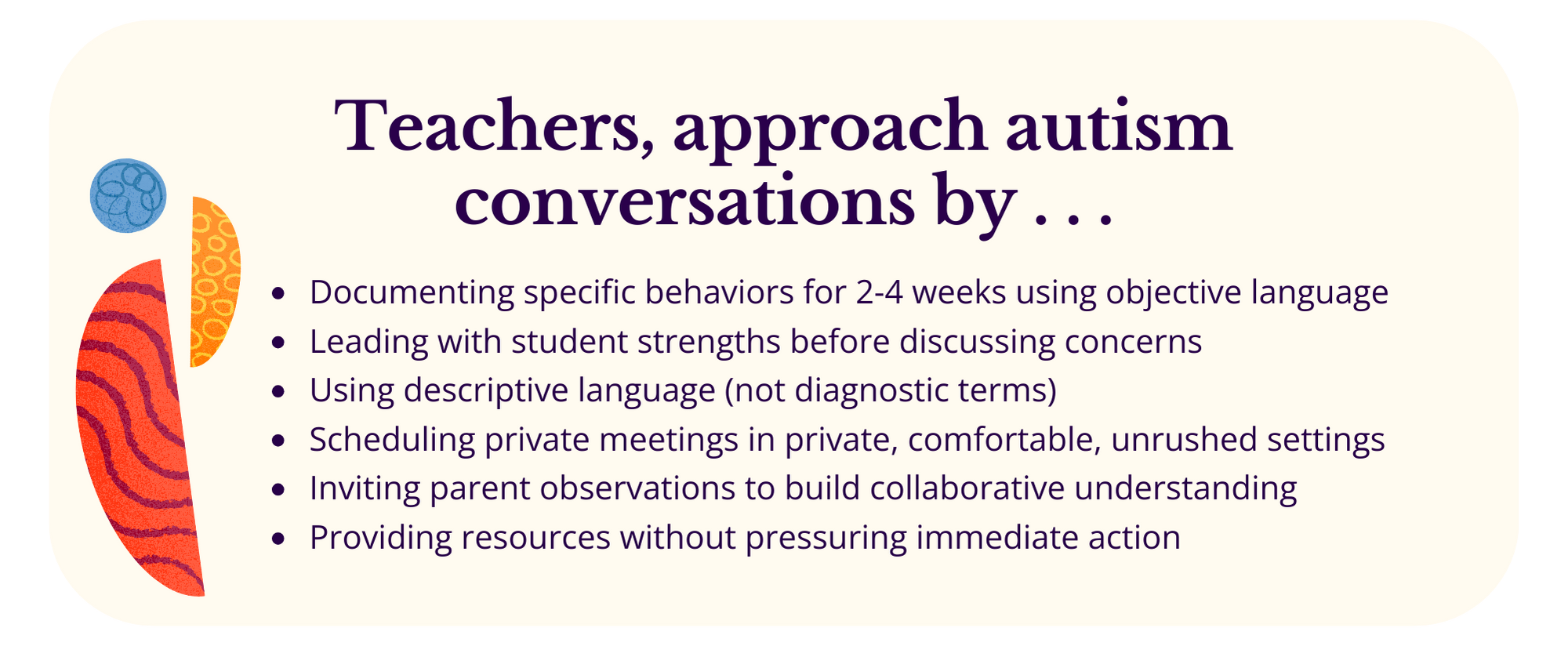

However, recognizing potential autism signs isn't the same as a diagnosis. And being familiar with some of the behaviors associated with autism is not the same as being equipped to diagnose. As a teacher, your important role is to observe, document, and share information that helps parents make informed decisions about their child's needs. While extremely valuable, your observations are just part of a larger puzzle.

Beginning your conversation

The most effective way to start your conversation about autism concerns is by highlighting the student’s strengths, interests, and what they enjoy or do well. This reassures parents that their child is valued in your classroom. It is also important to establish your professional boundaries clearly by stating that while you are a trained educator, you are not a clinical professional and therefore cannot make any kind of diagnosis. Emphasize that your role in the conversation is to share your observations as an expert educator who has come to know and observe their child during the school day, not to suggest or diagnose any particular conditions.

Sharing your observations

Think of your observations as information to explore together. Share documentation of your observations, including the student’s strengths, capabilities, preferences, and needs, alongside any observed behavioral and social communications patterns. Use factual, non-judgmental, non-clinical language. Avoid using the word “autism” or other diagnostic terms directly, instead discuss specific areas of concern that could relate to autism characteristics without making explicit diagnostic connections.

Frame your concerns as personal observations rather than professional assessments. Say, “Here is something that I noticed in the classroom” and pair this with specific examples of what you’ve seen. Focus on the child’s support needs rather than any shortcomings you perceive. Describe your concerns as potentially stemming from sensory needs, communication challenges, or socialization support requirements rather than using language that focuses on disruptive or unusual behaviors.

Asking questions, inviting input, and partnering with parents

The words you choose matter enormously. Use open-ended questions to invite collaborative exploration: "Are there any behaviors that your child has that you're concerned about?" or "Are there any challenges related to communication or socialization that you've noticed at home?" When sharing specific observations, frame them as invitations for discussion: "I've noticed they've had some difficulty making friends, have you seen anything similar at home?" or "I've observed some challenges with verbal communication, is this something you would be interested in getting some extra support around?"

Most importantly, make space for parents to share their own experiences. They know their child in ways you don't, and often they've been wondering about some of the same patterns you've noticed. When you approach the conversation as collaborative exploration rather than expert consultation, parents become your allies in understanding and supporting their child. The goal isn't to convince them of anything, it's to pool your observations and theirs to build a fuller picture together.

- Greeting and purpose: “Thank you for meeting with me. I wanted to talk about how [student’s name] is doing and share some observations from the classroom.”

- Strengths first: “I’ve noticed that [student’s name] really enjoys [activity] and is very good at [skill].”

- Share observations: “I’ve also observed that [student’s name] sometimes finds it challenging to [describe specific behavior], and I wanted to discuss this with you to see if you’ve noticed anything similar at home.”

- Invite input: “Have you noticed anything like this? How does [student’s name] interact with others at home?”

- Discuss next steps: “Sometimes, these behaviors can be part of a student’s unique way of developing, but they can also be signs that a student might benefit from extra support. Would you be open to exploring this further with a specialist?”

- Provide resources: “Here are some resources that explain more about student development and support options. I’m here to help you through this process.”

- Close with support: “I know this can be a lot to take in. Please let me know if you have questions or want to talk more. We’re here to support you and [student’s name].”

Blackbird experts share their experience

Through our understanding-first approach, we envision a world where every young person is fully understood and receives support building the tools they need to thrive.

"Access to comprehensive autism assessments should be a right, not a privilege. Evaluations must be affordable and conducted by experts who can distinguish autism from overlapping conditions like ADHD, anxiety, and trauma. In today’s post-pandemic world, where stress, disrupted development, and increased screen use blur the picture, this expertise is more important than ever."

Coleen Vanderbeek

Psy.D., LPC, ASDCS, IMH-e; Director of Learning and Development

"At Blackbird Health, a child is not a collection of separate issues; a child is a complex individual where learning, emotions, and physical well-being, strengths, and challenges are deeply intertwined. Our approach is centered on an integrated model that seeks to understand the whole child and address the root causes and co-conditions that affect any challenges. This is incredibly helpful for educators seeking to support their students comprehensively."

Amy Edgar

APRN, CRNP, FNP-C; Blackbird Health FounderWhen is the best time to talk to parents about autism concerns?

The best time to talk to parents about autism concerns is after you’ve had time to observe and document a clear and consistent pattern of behavior over at least 2-4 weeks, which allows you to distinguish between temporary adjustment behaviors (at the beginning of the school year, after holiday breaks, etc.) and ongoing patterns. However, consider having the conversation sooner if safety concerns arise, if the student appears significantly distressed or overwhelmed daily, or if you notice regression in previously demonstrated skills.

Sharing resources

You don’t need to become an expert on resources in your area, but having a list of helpful resources ready will be helpful if parents ask, “so now what?” Familiarize yourself with what your school district offers, local pediatricians who understand developmental concerns, and specialized clinics in your area. If you’re working with younger children, you can also refer parents to the CDC’s Learn the Signs. Act Early. When parents see that you’ve taken time to research next steps, it demonstrates your genuine commitment to supporting their family through this process.

For families in southeastern Pennsylvania and northern Virginia, Blackbird Health offers comprehensive autism evaluations and support services all in one place—from the initial assessment to ongoing therapy and even family counseling. Having a few options ready to share can help parents feel less overwhelmed about where to start.

How to handle parent reactions to autism discussions

Every parent will respond differently to these conversations, and that’s exactly as it should be. Some may feel relief that someone else has noticed what they’ve been wondering about privately. Others may feel shocked, defensive, or even angry—not at you necessarily, but at the situation itself.

The most powerful thing you can do in these moments is listen to what’s underneath their emotional response. When a parent seems overwhelmed, try reflecting back what you’re hearing. Don’t rush to minimize their feelings or quickly pivot to the practical next steps. Sometimes a parent needs silence and some time to gather themselves, and that’s okay. When you mirror a parent’s feeling, for example, saying that the concern sounds scary or that the parent seems relieved to finally have a word, the parent will feel understood and the conversation can move from emotion to practical steps.

Sample conversation structure

When parents show relief/were already wondering

Parent says: "I'm actually glad you brought this up. I've been wondering about some of these things myself."

Your response: "It sounds like you've been observing some similar patterns at home. That's really helpful information. Would you like to share what you've been noticing? Together we can think about what kind of support might be most helpful for [student's name]."

When parents are not open to talking or unresponsive

Parent says: "I don't really have any concerns about that" or becomes quiet and withdrawn.

Your response: "I understand this might not feel like a concern to you right now, and that's completely valid. I just wanted to share what I've been observing at school. Let's keep this in our minds for future conversations, and please know I'm always here if you want to discuss [student's name]'s progress."

When parents reference family history or friends

Your response: "That personal experience gives you valuable perspective on what to look for. What similarities have you noticed? It might be helpful to explore whether [student's name] could benefit from some of the same supports that have worked for [family member/friend's child]."

When parents flat-out deny

Parent says: "No, my kid doesn't have autism. I don't know why you're suggesting that."

Your response: "I hear you, and I want to be clear that I'm not suggesting any diagnosis. I'm just sharing some observations from the classroom about areas where [student's name] might benefit from additional support. Let's table this conversation for now, and we can always revisit it if you'd like to discuss it further in the future."

Remember, too, that parents and families bring their own cultural backgrounds and beliefs about developmental differences to these conversations. What feels supportive to one family might feel intrusive or inappropriate to another. Ask questions and take time to understand how a family’s background shapes their perspective, and adjust your approach accordingly. Respecting and understanding parents' cultural backgrounds and beliefs about developmental differences can help keep conversations respectful and effective.

Frequently asked questions

How do I start a conversation with parents about autism concerns?

Begin with what you observe, not conclusions. Use specific, objective language. Frame your communication as wanting to work together to support the student's success. Ask open-ended questions about what they've observed at home and what strategies work well. Emphasize your shared goal of helping their student thrive.

What should teachers never say when discussing autism concerns?

-

Avoid diagnostic or clinical language if you are not a qualified healthcare professional. Never suggest the student is being difficult or defiant when they might be struggling with sensory or communication challenges. Don't dismiss parents' concerns or observations, even if they differ from yours.

-

Avoid comparing the student negatively to peers or making the conversation feel like a list of deficits. Don't pressure parents into immediate action.

When should teachers wait vs. act immediately on autism concerns?

-

Act immediately if there are safety concerns, severe behavioral escalations that disrupt learning for everyone, or if the student seems distressed and current strategies aren't helping. Also act quickly if you notice significant regression in skills or new concerning behaviors.

-

Wait and observe longer if you're seeing inconsistent patterns, if the behaviors might be explained by recent changes (new school, family stress), or if you need more time to try different classroom strategies. Generally, document consistently for 2-4 weeks before initiating formal conversations, unless immediate safety or wellbeing concerns exist.

Moving forward together

These conversations about autism concerns—difficult as they are—create the conditions for genuine partnership between families and educators when handled thoughtfully. When you approach parents with care and focus on understanding rather than conclusions, trust develops and students benefit from having adults work together.

Yes, talking to parents about autism feels overwhelming. But your willingness to have this conversation, your observations, and genuine care can open doors to support that might otherwise remain closed. Remember: Your goal isn't to solve everything in one conversation—it's to build the understanding that makes everything else possible.

This article is for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult with your child's healthcare provider or a mental health professional for personalized guidance.

Bethany Barney, MSS, LCSW

Bethany Barney, MSS, LCSW is a Diagnostician and Director of Clinical Evaluation at Blackbird Health. With her specialization in neurodevelopmental disorders and child and adolescent mental health, she brings extensive expertise to comprehensive clinical assessments that help children and families access the support they need to thrive.

Need ADHD testing? We can help.

Share our contact information with a parent who may be considering an autism evaluation or to learn more about our services. To speak to a Blackbird Health Care Navigator, call (484) 202-0751 or email Blackbird Health at info@blackbirdhealth.com.